My Burn Story: A Crisis Communications Case Study

On June 24, 2008, my life changed when an eight gallon bucket of scalding chicken stock came tumbling down on my feet and ankles.

More on that – and the story of how the responsible party cost itself a lot of money through a flawed crisis communications strategy – in a moment.

First, the background. I’ve always loved cooking, and in 2008 decided to up my game by registering for professional cooking classes at New York’s French Culinary Institute. I continued to run my company during the day, and spent three evenings per week learning how to cook.

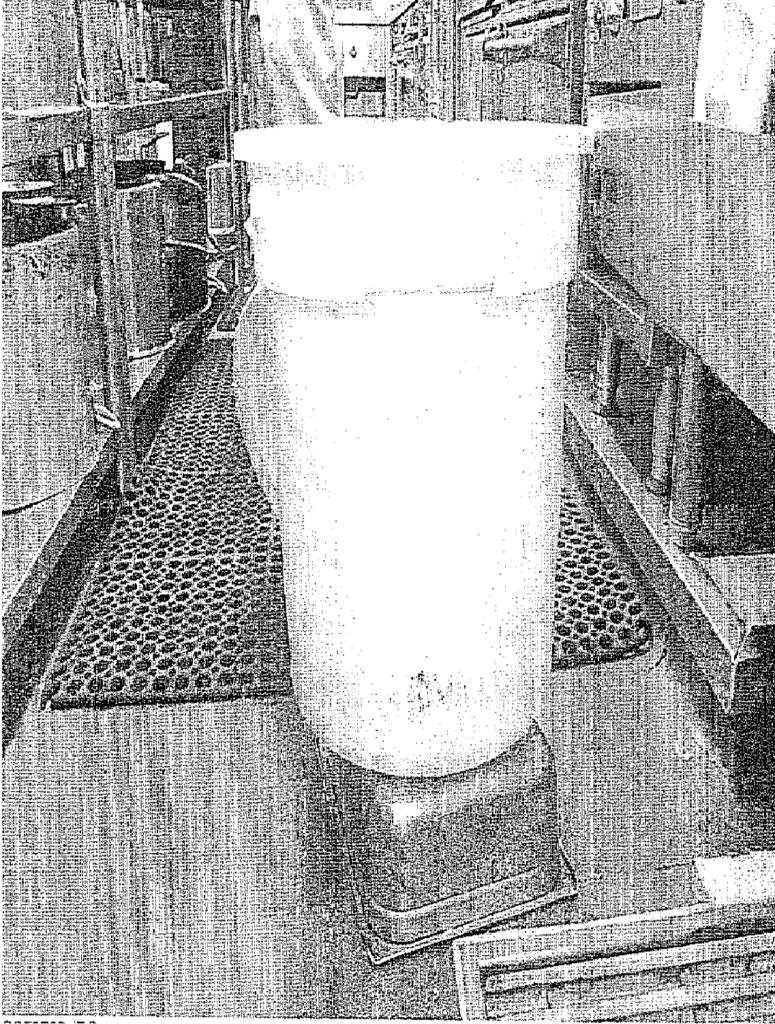

One night about five months into the class, I was cubing pork in the kitchen. Behind me, the chef-instructor began straining chicken stock by placing a bucket on top of an upside-down hotel pan. Unfortunately, the bottom of the bucket was larger than the hotel pan’s top, and the unevenly placed bucket toppled.

The bottom of the bucket was larger than the bottom of the hotel pan, causing it to tilt over when it filled.

I was about four feet away, my back to the bucket. I felt something hit my body, but it took my brain a couple of seconds to process what had happened. When the pain finally hit, it struck like a lightning bolt. I yelped, ran into a back hallway, and removed my shoes, socks, and pants. But it was too late. My socks had absorbed the hot liquid and held it against my feet for more than 30 seconds.

The school’s instructors called an ambulance and quickly placed my feet in an ice bath. I should have remembered that the school’s instruction manual specifically said not to use ice for a burn since it can deepen a burn, but I was in shock. The school’s instructors – the very people who taught that critical safety lesson to students on the first day of class – also forgot that lesson.

I spent two weeks in the New York Presbyterian Hospital Burn Unit. I couldn’t walk. And I won’t describe the pain, other than to say that Morphine and Percocet didn’t touch it.

As friends and family visited my hospital room, many of them asked whether I was going to sue the school for what clearly was their fault. I said no. I’ve always looked askance at America’s litigious culture, and didn’t want to be part of our flawed legal system. Accidents happen, I thought.

But no one from the French Culinary Institute called to see how I was doing. Day one, nothing. Day two, not a word. Still, I resisted calls from friends to speak with an attorney.

Finally, on day three, the school’s registrar called. I may have a word or two wrong, but the conversation went almost exactly like this:

Registrar: “How are you?”

Me: “Not good.”

Registrar: “Do you have insurance?”

Me, taken aback: “I thought the school’s student insurance policy covered accidents at the school?”

Registrar (scoffing/laughing): “No. We’re you’re secondary insurance.”

It was at that very moment that I decided to sue the school. By making it abundantly clear from the start that the school’s priority was their bottom line and not my health, I decided I should knock off the martyr act and prioritize my own self-interest.

Since this is a media training blog, here’s where the school went wrong from a crisis communications perspective:

1. They Waited Too Long: Despite suffering what many chefs told me was the worst injury in the history of the school, the school waited until my third day in the hospital to make its first official contact. The silence was deafening.

2. They Prioritized Self-Interest: If the registrar had to bring up insurance during our first phone call, why did she make it her second question and accompany her response with a scoffing laugh? Shouldn’t she have registered more genuine concern first?

3. They Didn’t Do Everything They Could Have: If I was advising a client in this situation, I would tell them to say something like this to the burn patient:

“You’re part of our family. We’re going to send meals from the school to you every day you’re in the hospital so you don’t have to eat hospital food. And please let me know if you have any special requests.”

Had the school done any of the above, I might not have sued, and the school’s insurance company could have saved some cash.

Once released from the hospital (still unable to walk without assistance), my quest for justice intensified as the school continued to mangle the situation. They refused to refund the prepaid portion of my tuition, didn’t reimburse my out-of-pocket expenses as promised, failed to use safety equipment that could have prevented the accident, didn’t conduct new safety courses to address burn care, and lied during the deposition (fortunately, my chef-instructor and her supervisor contradicted one another in their sworn testimony).

My attorney, Charles Gayner (the type of guy you want on your side if you’ve been wronged) kept fighting for a fair settlement – and we finally agreed to accept the other side’s offer last month, just hours before jury selection was set to begin. They clearly seemed to realize their case was a loser.

Conclusion

Today, more than three years after the accident, I’m okay. It’s still a bit uncomfortable to stand motionless for long periods of time, so packed trains and cocktail parties can be challenging. But if you didn’t know this story, you’d never know it by looking at me. I can hide my symptoms fine.

I could have added a number four to the above list, as well.

4. No One Said “I’m Sorry:” Yes, I know the standard playbook says not to admit guilt, and that doing so can lead to the termination of your insurance policy. Therefore, for legal reasons, I didn’t expect the French Culinary Institute to apologize. But now that the case has settled and the school is protected against any future claims, they still haven’t apologized. UPDATE: See comment section for an update.

One final note: The school’s insurance company could have legally prevented me from writing this story by requesting a nondisclosure agreement as part of the settlement. I was prepared to sign it, but they never requested it. As a result, the school will likely suffer additional – and completely unnecessary – reputational damage. I’m delighted the insurance company didn’t ask for it – but as a crisis counselor, I’m stunned by their oversight.

Editor’s Note: The dimensions on the first photo in the story are a little distorted – the bucket is actually a bit flatter and shorter than it appears here. My photo software couldn’t get this image quite right, but I decided to run it anyway since both versions showed the important point: that the top of the bucket was smaller than the bottom of the bucket. I’d be happy to email anyone the PDF with the original photo for their inspection upon request.

Dear Brad,

Thank you for sharing this interesting, personal story. I’m sorry you were burned.

As an attorney myself, I understand the thinking behind the “don’t say you’re sorry” rule. Personally, although it is a good rule, it’s a bit overblown and it needs a corollary.

If you say “I’m sorry”, it doesn’t mean you’re going to lose the case no matter what.

I tell clients to say (and to tell their staff to say), “I’m sorry this happened.” Although unlikely, if the injured party says, “Aha! So, you admit this is your fault;” or, “So, you admit you did this on purpose”, then say, “No, I didn’t say that; I’m just saying I’m sorry this happened to you regardless of who is at fault.”

David,

Thank you for your comment. You’re exactly right. I knew enough not to expect an apology – but genuine compassion preceding “do you have insurance?” would have gone a long way.

I should note that some of my fellow students and chefs were great. The same can’t be said for the administration.

Best wishes,

Brad

Hi Brad,

Thank you for sharing this story, both here and when we were able to catch up with you this weekend.

Lots of valuable lessons here . . . not just on media relation but also on how we can all treat each other a bit better despite the legalities of a situation.

It is so great to be back in touch. Look forward to seeing you again soon.

Brad, what a story! Thank you for sharing. I’m so sorry you got burned and regret that it now affects your ability to stand for long periods. But I’m so glad you exacted sweet revenge. And the kicker — their failing to require a DND agreement –just makes the revenge even sweeter. I hope all of your friends spread this story far and wide. I’ve already shared it.

Thanks, Michelle!

I consider myself lucky – I can do virtually everything I used to be able to, minus going to standing-room only events (I can do it if necessary, but it stresses me out a bit). I have to admit I was surprised by the lack of a “Do Not Disclose” agreement – after three years, you would have thought they would have known I specialized in media and crisis communications! But as you pointed out, their ineptitude is my gain.

No word from the school yet, and sadly, I never expect to hear from them. As Elton John once sang, sorry seems to be the hardest word.

Brad

Brad,

Let me simply say “I’m sorry.”

Your accident is the only one of it’s kind at the French Culinary Institute in almost 30 years. As you know, our Chefs are passionate about our students, and I believe they did everything possible to attend to you while medical help arrived.

Brad, I know this was a very traumatic experience for you. As you may not have been aware due to your condition, our VP of Student Affairs, Christopher Pagagni was with you at the hospital shortly after you arrived, and our President, Mr. Apito came to see you as well.

But my purpose in responding is not to debate visits. I want to keep this short and just let you know publicly that I’m am sorry for your pain and time away from your culinary passion. I wish you well.

Dorothy Cann Hamilton

Founder, The French Culinary Institute

Earlier today, I called Ms. Hamilton’s office to speak with her personally. She returned the call within an hour.

After discussing several matters with her, she offered to host an event at the FCI for a charity I’m involved with, The Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors. I appreciate her kind offer.

Still, I continue to maintain that the school could have handled the situation better. I am disappointed with Ms. Hamilton’s reply that the school did “everything possible to attend to [me] while medical help arrived.” In fact, page seven of the school’s student textbook states specifically that burns should not be treated in ice, as they can deepen the burn. I wish the school had used this incident as an opportunity to retrain its staff instead of defending an unsound medical care policy.

Still, Ms. Hamilton was sincere on the phone and sounded genuinely pained by my story. I appreciate her call.

Brad

Wow, that’s terrible story. Glad you are feeling better. You’ll be interested in this story from the NY Times – says number of medical malpractice cases goes down when doctors apologize. Who woulda thunk it?

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/18/us/18apology.html?pagewanted=all

What intrigues me now is that there is no more French Culinary Institute. You search and now get International Culinary Center. No more Mario Batali’s endorsements or mention of the French Culinary Institute. Whatever happened? it remains a mistery….

I am a graduate of the French culinary institute and it was an amazing experience. It sucks that happened to you but I know just from my experience they were always helpful. Also gustavo Anthony Bourdain is in a video endorsing the school so I don’t know what you are trying to get at?