Has Donald Trump Changed Media Training Forever?

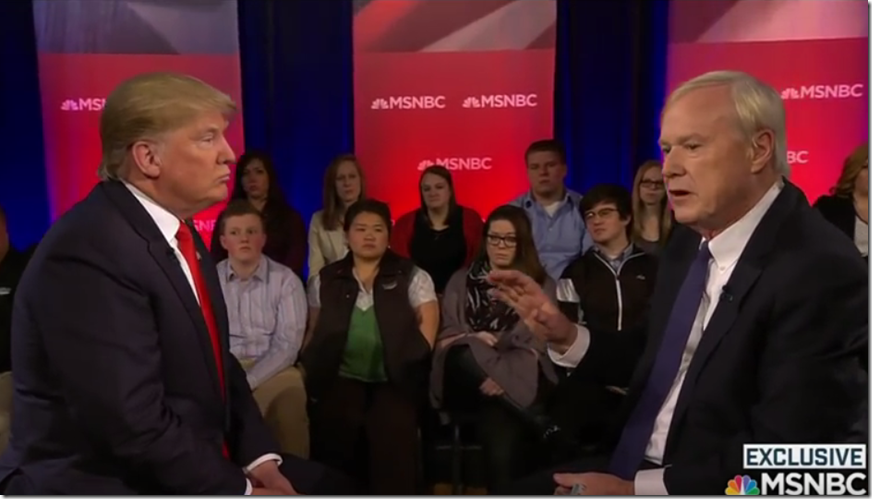

No question has dominated my professional conversations more lately than this: What does Donald Trump mean for media training?

It’s a good question. Mr. Trump has flouted the conventional rules we’ve taught in media training workshops for a generation and still managed to become the Republican nominee.

When people ask me whether Trump has changed the game forever, I always begin with the true answer: we don’t know yet. He earned the nomination—relatively easily—while embracing conspiracy theories, using unusually coarse language, and employing persuasion techniques rarely associated with presidential campaigns. Political scientists will be studying this campaign for decades—and even then, I suspect different analysts will reach different conclusions.

But I then offer a more substantive response: No, he probably hasn’t changed media training forever. But also, yes, he probably has.

No, Trump Hasn’t Changed Media Training

I remain skeptical of how much the conditions that permitted Mr. Trump’s rise extend to the less political worlds of business, nonprofit organizations, trade associations, and the like.

General elections are, for the most part, binary choices. The vast majority of voters will cast their ballots for Trump or Clinton (the Libertarian and Green Party candidates currently register a combined 12 percent).

Many of the people who end up voting for Trump don’t particularly like him—but really loathe Clinton. The reverse is also true—many people skeptical of Clinton will cast a ballot for her anyway to prevent Trump from entering the White House. Even many voters who generally prefer third-party alternatives will switch to one of the two main candidates so they don’t “waste” their votes.

But that same dynamic rarely exists in the non-political real world. If Coca Cola and Pepsi both alienate huge swaths of their consumer base, Dr. Pepper, RC Cola and many smaller brands would experience a sales surge. No one who dislikes Pepsi is going to buy it anyway just to prevent Coca Cola from making another sale.

Sure, a few brands may look at Trump’s success and emulate it. When Chick-fil-A alienated a wing of its customer base a few years ago by opposing gay marriage, its supporters flocked to its restaurants in solidarity; the pickle-happy chain’s sales actually increased following that controversy. In fairness, the chain wasn’t courting controversy in a Trumpian manner—but the case study suggests there’s room to alienate a significant portion of a customer base, rally and strengthen the existing portion of the base, and come out ahead.

But most companies and nonprofits don’t operate in that environment. They typically want to maintain a broad customer or donor base, prevent unflattering headlines, and avoid alienating current and potential supporters. For the brands who fall into that category, Trump’s techniques are anathema to their success.

One final note: it’s true that Trump defeated 16 primary opponents, which would seem to invalidate parts of my analysis above. But a late June poll found that more Republican voters would have preferred a nominee other than Trump. Again, that’s just not a business model most non-political groups would hope to embrace. Imagine 50 percent of the public refusing to even walk into their local shopping mall’s The Gap store simply because the brand’s public bombast had alienated them. And that doesn’t even address the potential risks to hiring, litigation due to discrimination claims, stock price, the availability of private equity, etc.

Yes, Trump Has Changed Media Training

For many years, I’ve been talking and writing about “gaffes”—both in and outside of politics.

During the 2012 campaign, for example, I wrote about several of Mitt Romney’s gaffes, including his infamous statement, “I like being able to fire people.” In context, he was making a valid point—people should be able to fire service providers who provide inferior service—but out of context, it just sounded bad and seemed to reinforce a narrative of a clueless candidate. Other quotes, about Michigan’s trees being the right height and his wife owning two Cadillacs, also earned a lot of airtime.

President Obama was also castigated for his 2012 quote that, “The private sector is doing fine.” That, too, was true by several metrics—but it felt off to millions of Americans still struggling through a slow recovery. His line, “If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that; somebody else made that happen” was deemed so off-note that it became a central theme of the 2012 Republican convention, even though that line, too, meant something different in context.

In hindsight, all of those gaffes seem downright petty compared to many of Trump’s. Neither Romney nor Obama mocked a disabled reporter, bragged about the size of his penis, called Mexicans rapists, said “pussy” during a public event, and so on.

As a result, I’ve reconsidered what I consider to be a “gaffe.” I don’t write about them as much as I used to, because the ones that are mostly the result of inelegant syntax no longer rate. And you know what? I think that’s a good thing. Perhaps we should forgive politicians, who are filmed for hours each day for months while sleeping far less than they should, for saying things inartfully once in a while.

We should make a distinction between gaffes of malice and gaffes of imperfection. I suspect millions of Americans, after watching this campaign, would agree—and will turn a skeptical eye toward a media that is on constant gaffe patrol, particularly for the silly stuff. If I’m right, that trend will diminish the impact of many gaffes that would have hurt politicians more just a few years ago.

This post isn’t meant to be comprehensive—I didn’t even touch on racial tensions, terrorism, economic insecurity, “political correctness,” and a host of other relevant factors influencing Trump’s success. So please add your thoughts in the comments section below about whether or not you think Trump’s approach has changed media training—and if so, how?

Brad,

I absolutely do not think that Trump has changed media training. He has changed politics THIS CYCLE. No other politician is like him or more importantly, wants to be like him. He has succeeded with a portion of the electorate who was clamoring for a outsized personality who promises what they want to hear. The media training that you do is directed at normal people who speak for their organizations. It will never be acceptable for an organization to belittle and insult anyone, especially using easily proved lies.

Best,

Deborah

A unique set of circumstances has changed things in this instance. The electorate are tired of politicians who say nothing and seem to stand for nothing. The spin masters must take some of the blame for that. Too much polish has rubbed out any visible commitment to a cause. That’s why Brexit voters ignored all the ‘expert’ opinion in the UK, dynamic seems very similar to Trump campaign success. All Media training should be based on honesty, maybe we forgot that?

Applaud the attempt to analyze a campaign that has defied many conventions. Number 1 rule of comms still stands here — know your audience, and Trump does. His supporters seem to have lost trust in the impotent eloquence of politicians whose self-serving brand of statesmanship only serves for re-election. So far, he’s convinced them he can address their problems in a way that resonates and they’ve been forgiving of the gaffes. He’s leveraged that to completely dominate several news cycles and earn greater trust in his constituency for not backing down in the face of criticism. His downfall will come if the opposition is ever successful in creating the perception that he’s weak and/or selling them out.